iGoat Challenge Write up

Introduction

10+ years ago, before I moved into information security, I was a mobile application developer for a few years. I wrote native Android and iOS Applications using Java and Objective-C, respectively. A few weeks ago I attended a mobile application developer user group meeting during which I saw how far native mobile application development has come in the decade since I last did it. It was remarkable to me how well designed and easy it seemed to use SwiftUI and Swift versus interface builder and objective-c.

As a result of this discovery, I decided to look into modern mobile application security. I want to give a presentation on iOS application security to this user group at some point, so I considered writing some vulnerable application to demonstrate the various types of vulnerabilities that occur in mobile applications. Before I started though, I realized that someone else had probably created a “Damn Vulnerable”-type iOS application that I could leverage instead of writing my own. I found two:

This blog post will use the OWASP iGoat-Swift application to solve a few of the exercizes.

Setup

I used Xcode 15.4 targeting iOS 17.5, which is the very latest and greatest version released just earlier this week. With this bleeding edge version of XCode, I was not able to make CocoaPods link properly no matter what I tried. I decided to fork the project, rip out the cocoapods implementation, and recreate the dependencies within the XCode Dependency Management tool. I tried to do this with both DVIA-v2 and iGoat-Swift; in the end I went with the OWASP project because it only had one dependency (RealmSwift) to recreate. If you are interested, my forked repository is located here: https://github.com/nstarke/iGoat-Swift.

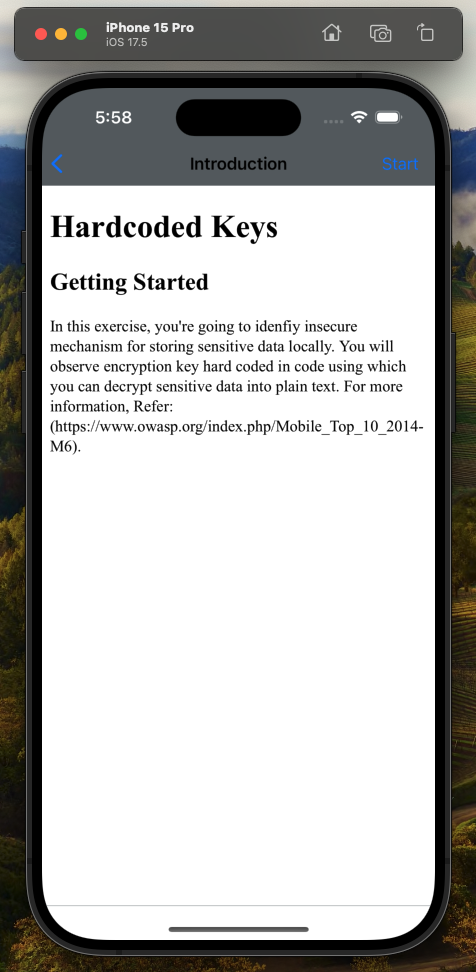

Challenge: Hardcoded Keys

One of the problems I have consistently seen with client-side software, especially native Android/iOS applications, is the use of hardcoded secrets and keys. I decided to start with this challenge since it is so common.

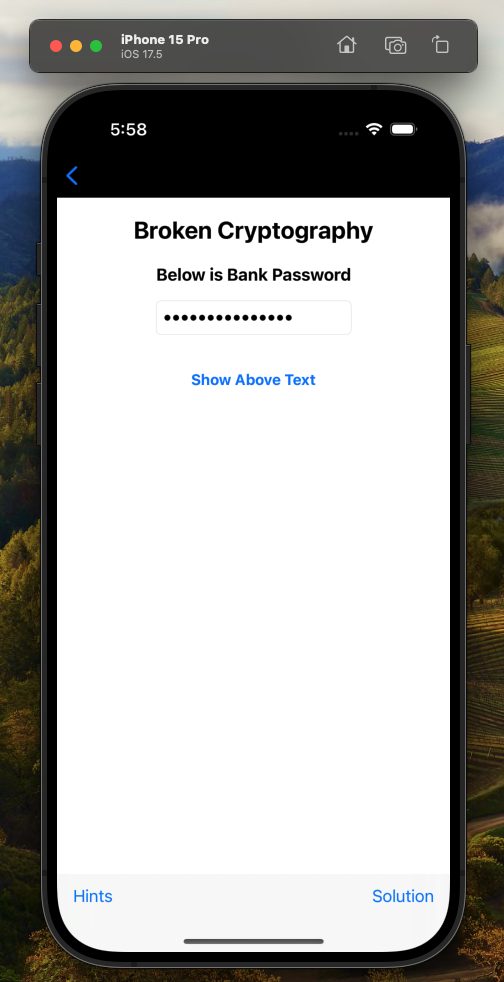

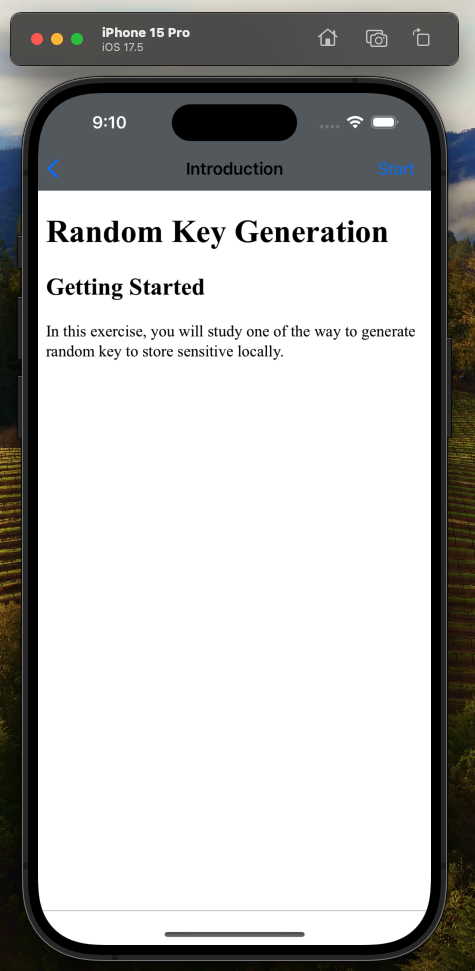

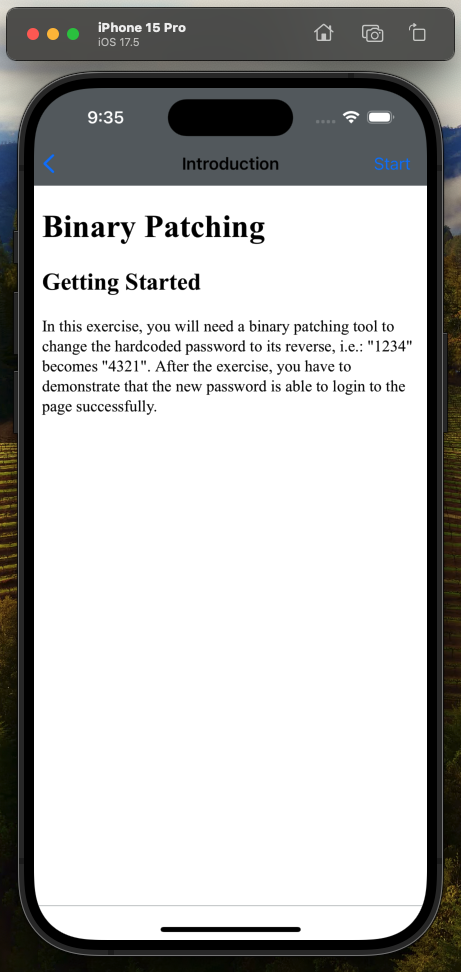

The challenge is to find the hardcoded password for the BrokenCryptography exercize. In the application, it looks like this:

On this screen I can press start and the application will load the challenge view:

The challenge is asking us to dig through the source code and find the hardcoded password. I decided to take a slight departure here; since we are building debug versions of the iOS application, I thought it might be fun to show how to complete this challenge using Ghidra. With debug versions of iOS applications, the application builds are not encrypted with a per-device key like they are on production devices. Thus, it is easy to load them into Ghidra to perform binary reverse engineering to complete this challenge.

For those interested, it is fairly difficult to snag an unencrypted version of an iOS application binary. The process to do so generally involves a Jailbroken iOS device along with tools like Frida. I have found the process to be tedious and also well documented elswhere, so I’m going to skip that for this post.

By navigating in Xcode to Product->Show Build Folder in Finder, we can see where on the development host filesystem the application binary is located. Within the iGoat-Swift.app application folder, there is the actual binary Mach-O file we load into Ghidra:

$ file iGoat-Swift

iGoat-Swift: Mach-O 64-bit x86_64 executable, flags:

<NOUNDEFS|DYLDLINK|TWOLEVEL|WEAK_DEFINES|BINDS_TO_WEAK|PIE>

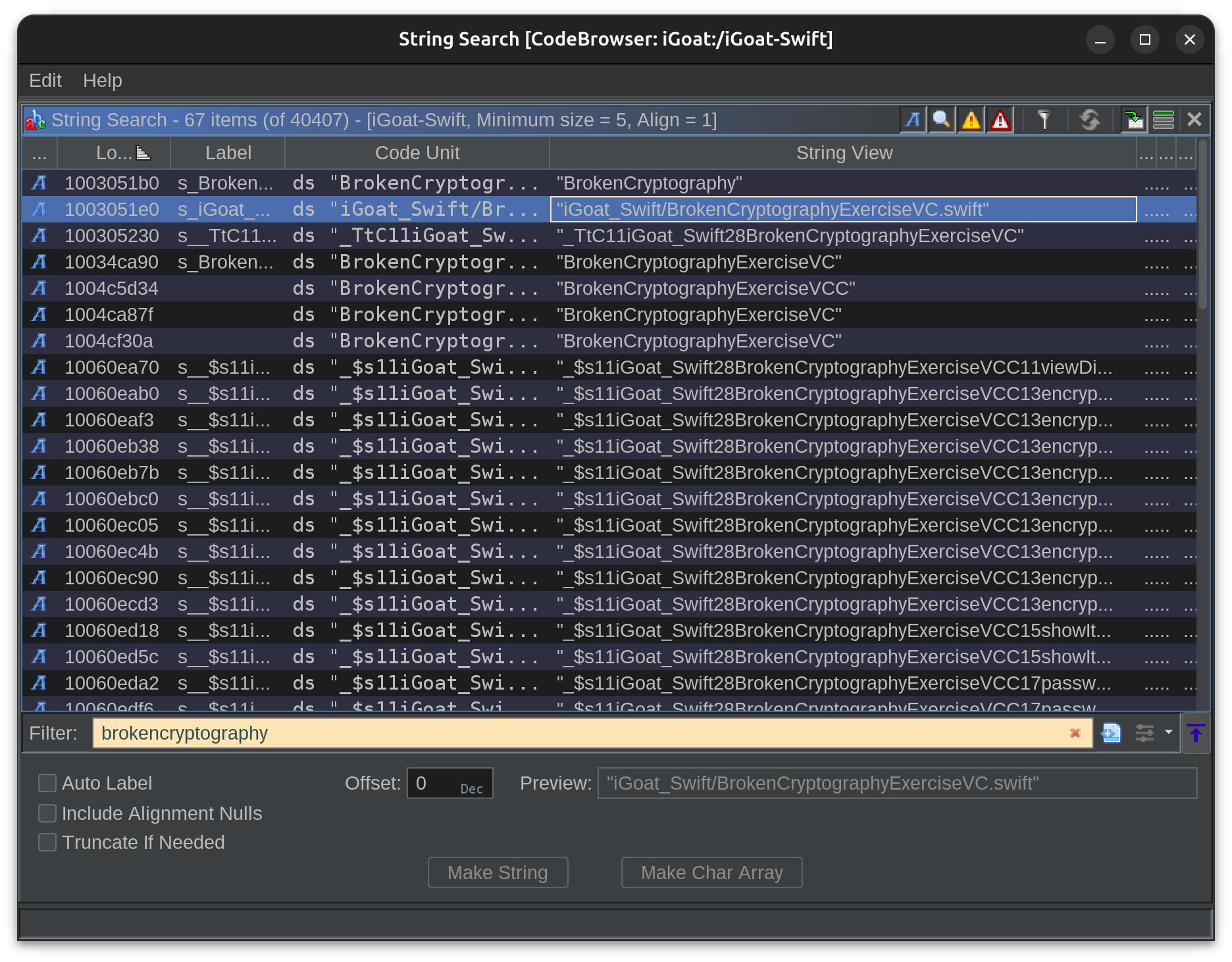

Ghidra

Once I had the application loaded and analyzed in Ghidra, I began searching for “landmarks”. Landmarks are identifiers or keywords I use to narrow down where I need to look in a given binary. In this example, I used the word Broken (as in Broken Cryptography) to find the general area in terms of functions where the relevant code resides.

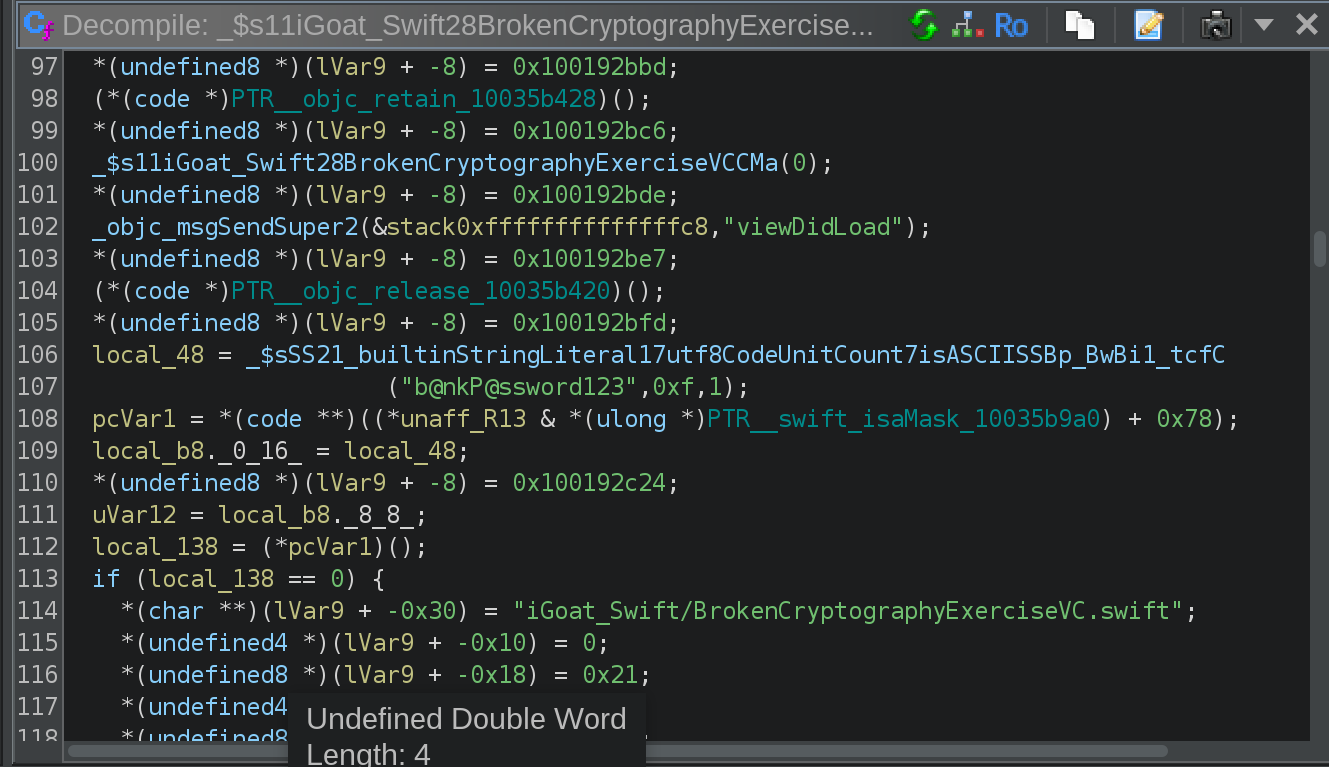

The second result caught my eye because of the .swift extension. So I navigated to that string and then looked at the cross references. This lead me to the function _$s11iGoat_Swift28BrokenCryptographyExerciseVCC11viewDidLoadyyF:

As you can see a few lines above the string location, there is something interesting:

local_48 = _$sSS21_builtinStringLiteral17utf8CodeUnitCount7isASCIISSBp_BwBi1_tcfC("b@nkP@ssword123",0xf,1);

Et Voila, there is our hardcoded password!

Challenge: Random Key Generation

The next challenge I’d like to look at is the “Random Key Generation” challenge:

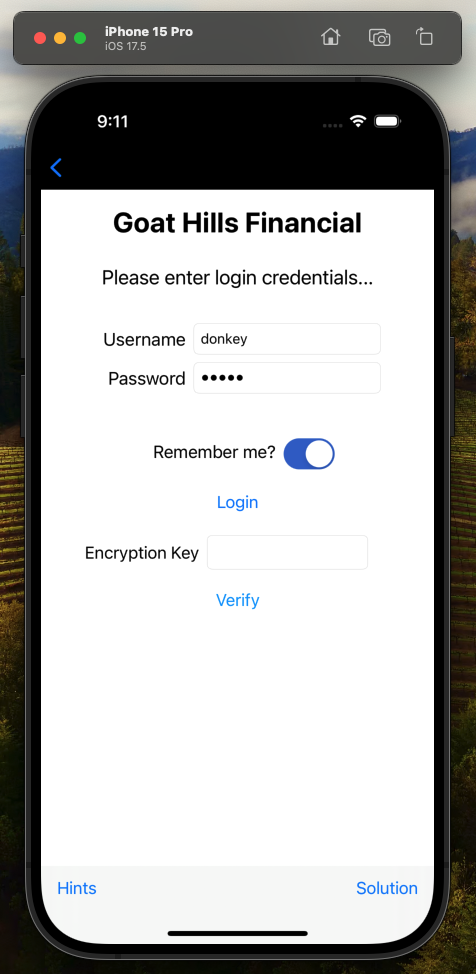

This challenge focuses on using side channels to recover random keys. The exercize presents a login form for a bank (“Goat Hills Financial”) and the idea is that an additional encryption key is necessary in order to complete the challenge.

The username and password fields are already filled in, so the first thing I tried was to press the Login button. When I did that, the application simulated an HTTP POST to authenticate the credentials, and then generated a random key to be used with the Encryption Key field to pass/fail the challenge.

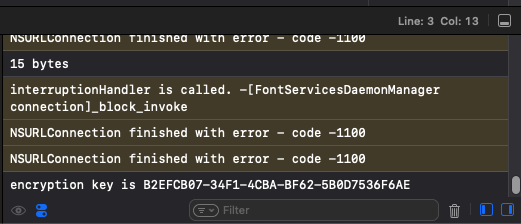

I noticed after I pressed Login that the username and password fields were emptied, and then I saw this in the XCode Application Output window:

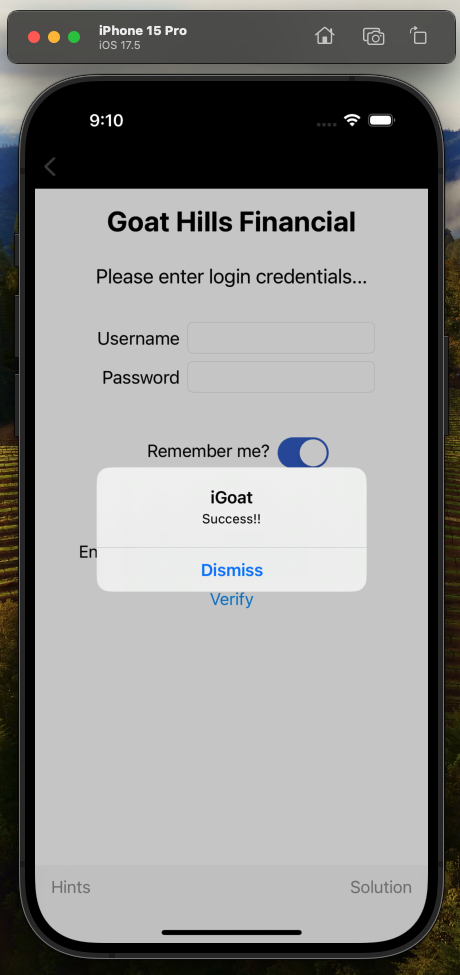

That UUID is the solution to the challenge. I copied the UUID onto the clipboard and then into the Encryption Key field and then pressed Verify

I tried looking on the filesystem in ~/Library/Logs/CoreSimulator for the UUID, but I didn’t see any files containing that string value. My check was cursory, and I’m sure the application output logs are stored somewhere in the ~/Library directory but my quick grep did not reveal where.

Challenge: Binary Patching

This challenge asks that we take the hardcoded password and reverse the password string in the binary and thus have the running application accept the reversed password string as the “correct” password.

Let’s take a look at the source code:

import UIKit

class BinaryPatchingVC: UIViewController {

@IBOutlet weak var passwordTextField: UITextField!

@IBAction func loginItemPressed() {

if passwordTextField.text?.isEmpty ?? true {

UIAlertController.showAlertWith(title: "iGoat", message: "Password Field empty!!")

}

let password = passwordTextField.text!

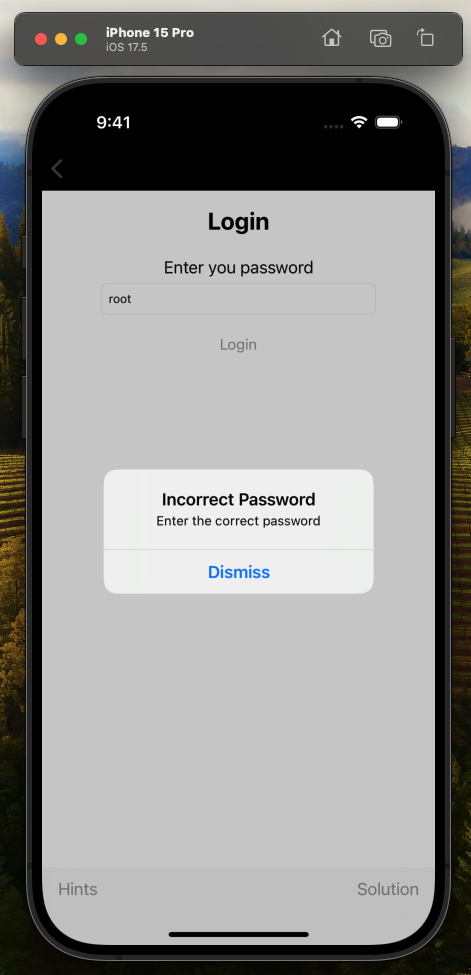

if password == "root" {

UIAlertController.showAlertWith(title: "Incorrect Password", message: "Enter the correct password")

return

}

UIAlertController.showAlertWith(title: "iGoat", message: "Congratulations")

}

}

In this code, the user-supplied password value is checked to equal the string root and if so it displays an Incorrect Password warning. It seems to me the logic is reversed here; that the line should read if password != "root" {, so we are going to assume the string we need to reverse is root even though it shows an Incorrect Password prompt.

The rest of this task will require Ghidra!

Ghidra: Binary Patching

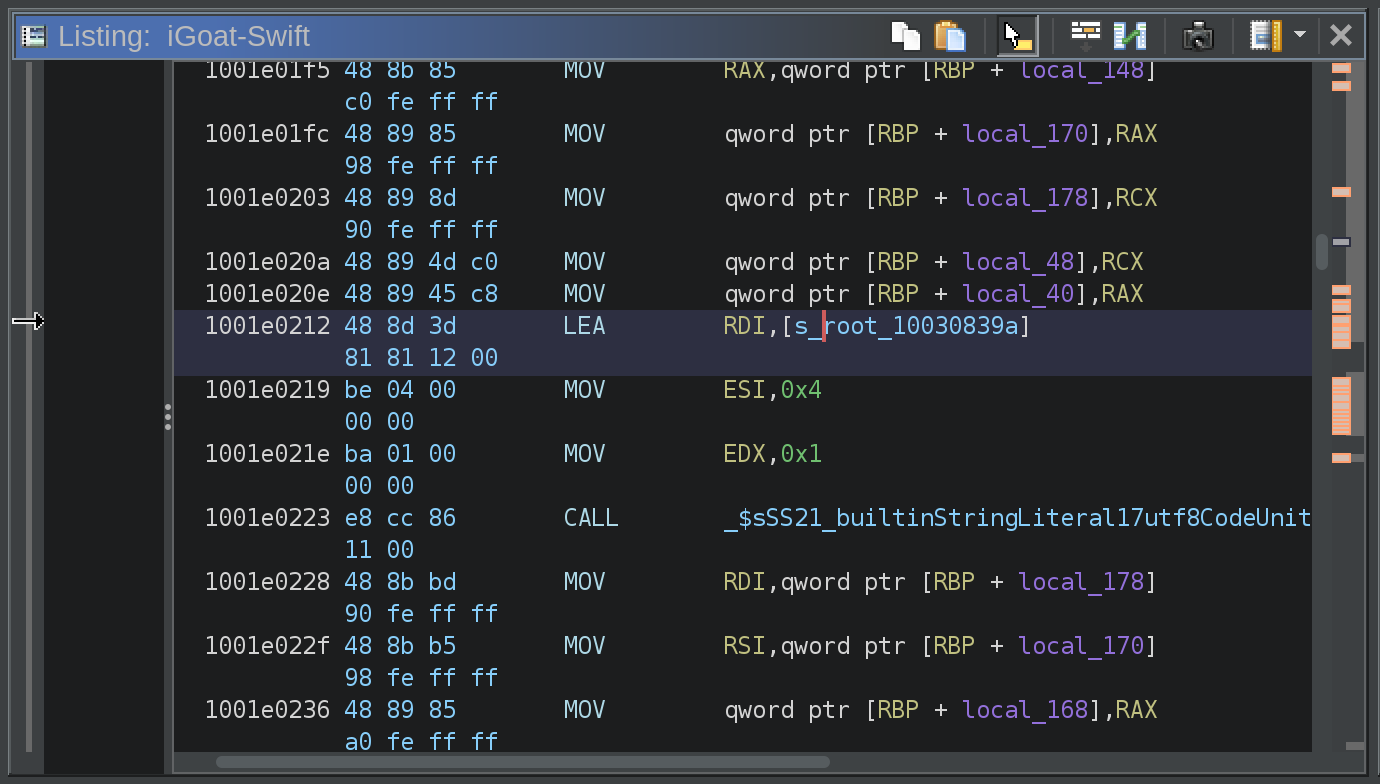

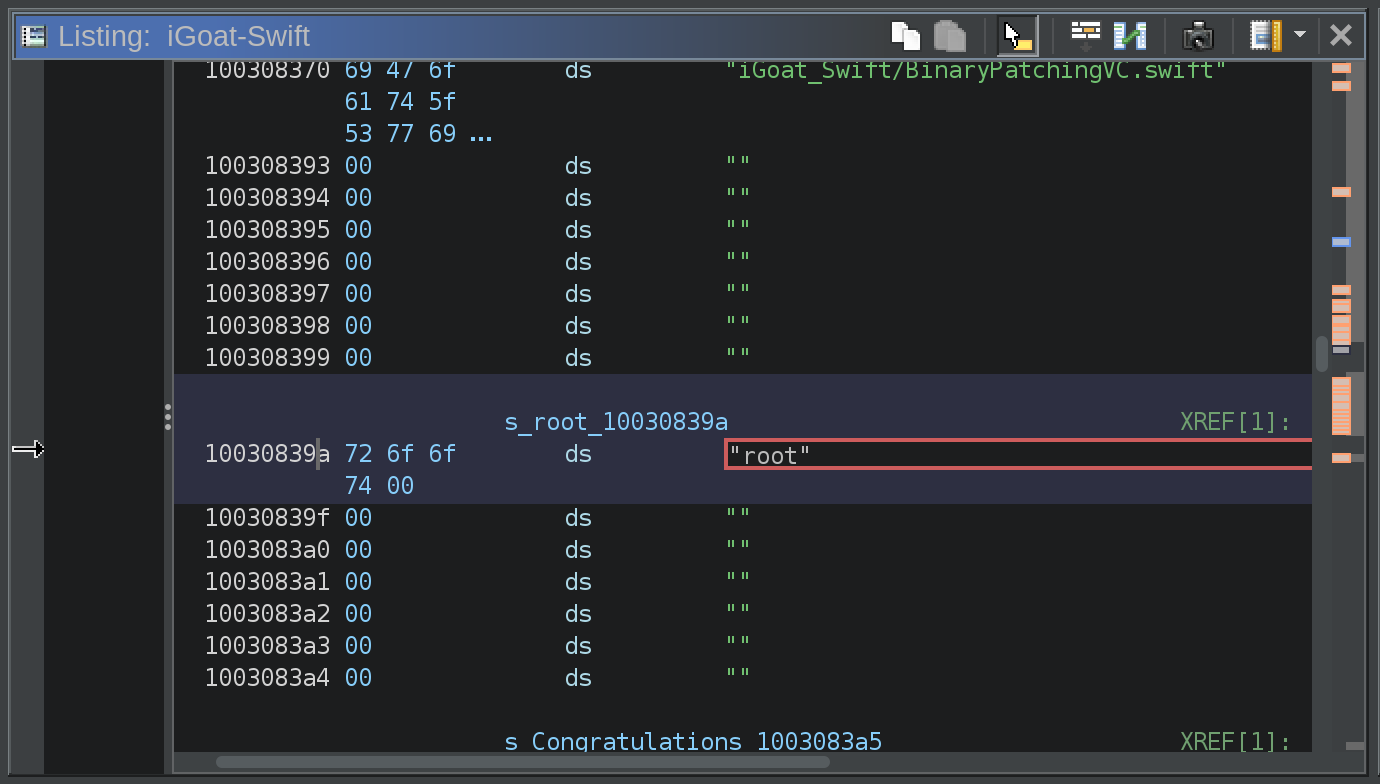

We can open Ghidra and import the iOS application binary into it. After analysis, I searched for BinaryPatching and found a symbol location for iGoat_Swift/BinaryPatchingVC.swift. This took me to a function called _$s11iGoat_Swift16BinaryPatchingVCC16loginItemPressedyyF. In this function, I located the hard coded string root in the disassembly view.

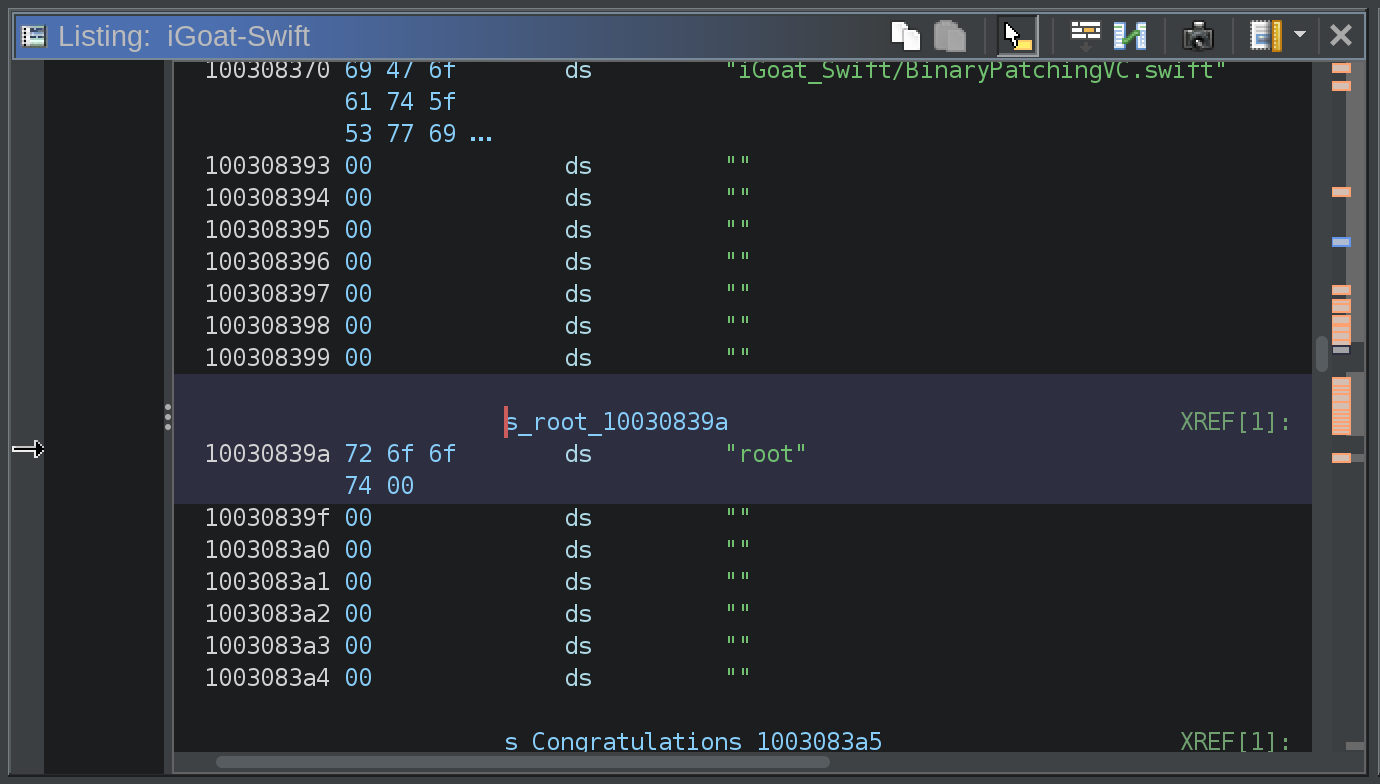

I then navigate to the location of the root string within the binary

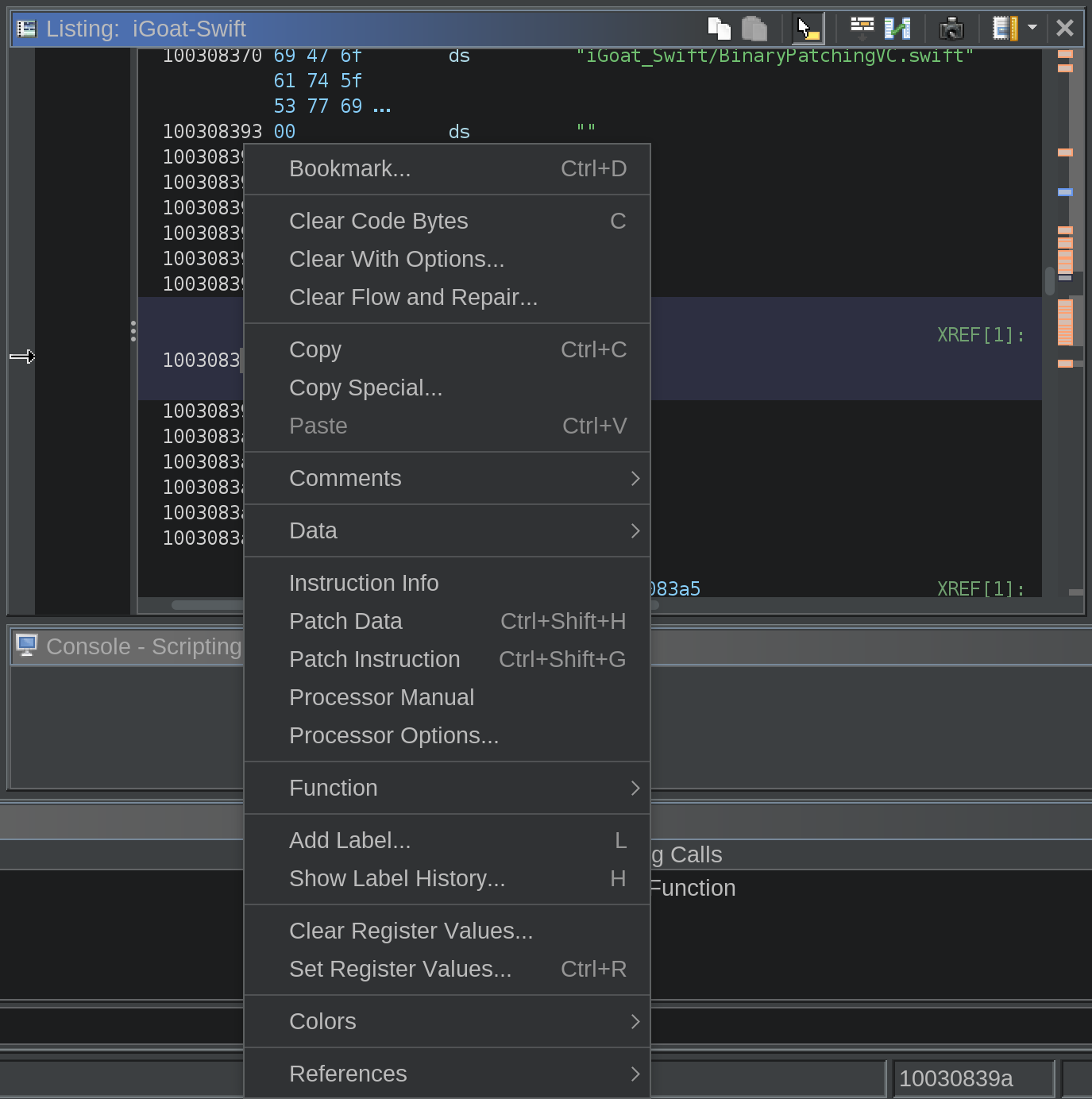

Then, I right click on the memory address of the string and select Patch Data from the context menu

This then allows me to type in the value I want.

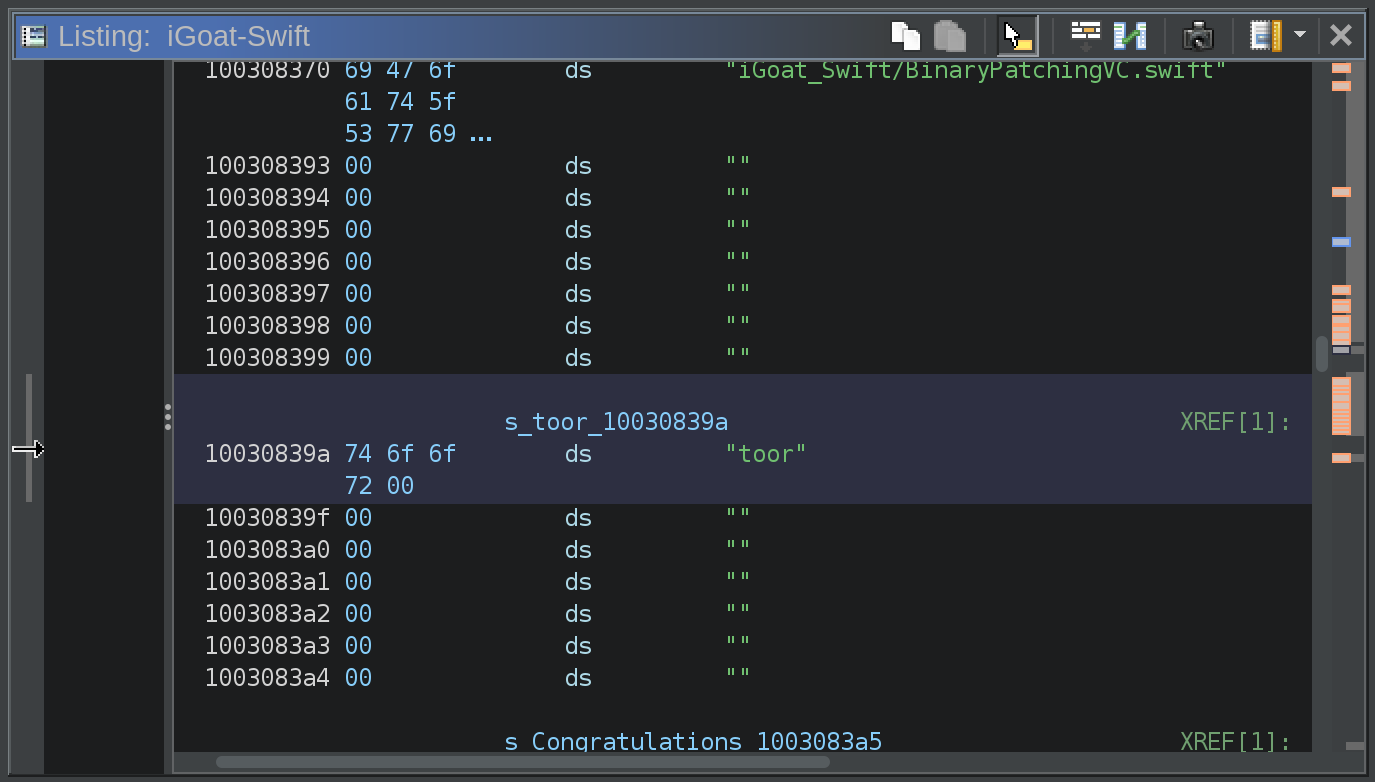

At this point, I change the value to toor

Then in Ghidra, I choose File->Export and export the program as raw bytes. We can then navigate to the iGoat-Swift.app directory and replace the iGoat-Swift file with our modified binary program file.

After that, on a Mac computer, we need to resign the iGoat-Swift.app directory for it to run properly with our modifications in the iOS Simulator. We can do this by running the following command on the Mac developer host:

codesign -s "Apple Development: Nicholas Starke" -f --preserve-metadata --generate-entitlement-der iGoat-Swift.app

Note that this requires an apple developer provisioning profile, which can be provisioned in Xcode.

After we have resigned our modified iOS application, we can drag from finder to the iOS Simulator and thereby install our modified application. Make sure you delete the original application installation first, as they will use the same bundle identifier.

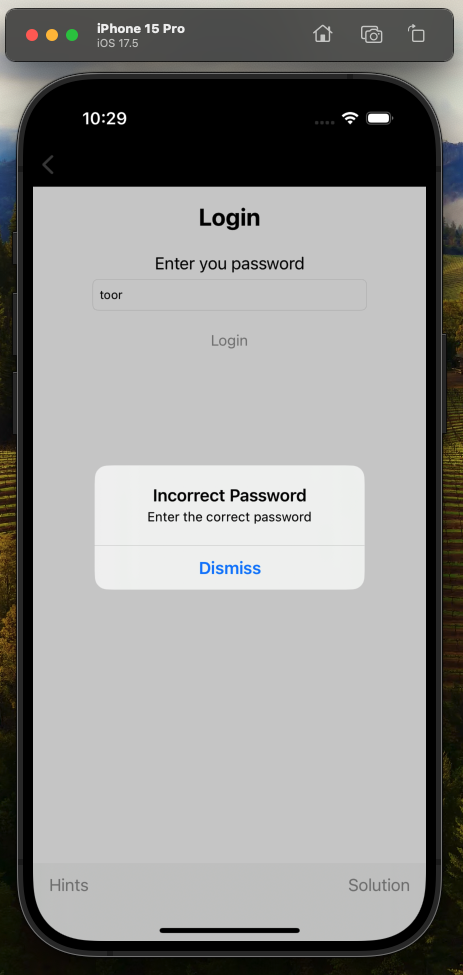

Once the modified app is installed and launched, I then navigate to the Binary Patching exercise, enter the password toor and receive the same Incorrect Password prompt as we did when we tried root before.

Summary

There are numerous other challenges in iGoat-Swift. I had a lot of fun working through and writing up these three, and if there is interest I will write up more of the challenges. Reach out if you have questions!